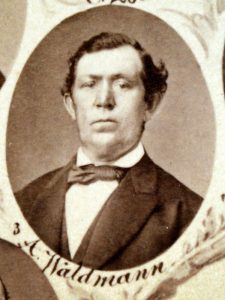

Anton Waldmann was born on December 4, 1823 in Kleinostheim, Germany near Aschaffenburg in Lower Franconia, a northern part of Bavaria. The son of farmers Johann and Anna Maria (nee Herzog) Waldmann, Anton was actually christened “Leonhard” at birth. He was the second oldest of five siblings, including an older sister Barbara who was denied an emigration permit and later committed suicide, a younger brother Michael who married and moved to Fuerth/Odenwald, a second younger brother Johann who died at the age of 29 in Kleinostheim, and younger twin sisters Margaretha and Eva, only the latter of which survived into adulthood. Anton was trained as a shoemaker in Klienostheim—which suggests he had no expectation of inheriting land from his father, who was likely a tenant farmer.

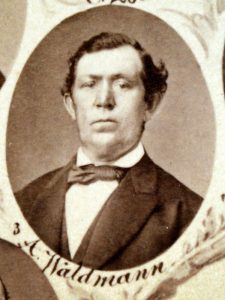

Anton Waldmann

Perhaps for this reason, in May of 1853, Anton emigrated to the United States. He met and married his wife Wilhelmine (“Mina”) Porth, who was born in Mirow, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany in 1826, somewhere in the U.S. While their path to the Upper Midwest is unclear, the couple arrived in St. Paul before the fall of 1856, by which time Anton was already profitably engaged selling fuel wood to steamboats from a warehouse on the Upper Levee. The steamboat trade was approaching an all-time high, with 759 steamboats landing in St. Paul that year, and 965 landings in 1857—both record years that would end with the financial Panic of 1857.

Original stencil for an Anton Waldmann keg found on premises

On March 23, 1858, Anton petitioned the Common Council of St. Paul for a liquor license to run his lager beer saloon. It was a time when Temperance proponents had gained influence over the Council and other key offices, ultimately pressuring the City Marshall and his deputies to clamp down on the dozens of unlicensed saloons operating throughout the City. Waldmann himself seems to have been caught in the crackdown, since records indicate he was required to pay for a license extending back six months—suggesting that he had opened his saloon sometime in October of 1857 without a license. Waldmann dutifully renewed his license in April of 1859. The following year, the Minnesota Legislature passed a law prohibiting cities and counties from imposing licensing fees or taxes on the manufacture or sale of lager beer in Minnesota. While this so-called “Lager Beer Act” was repealed in 1862, Waldmann never bothered to apply for another liquor license—by the following year he had opened a flour and feed store on Third near Eagle Street.

Waldmann’s saloon was short-lived (1857-1863), but it must have been profitable. In October of 1859, at a time when the rest of the country had barely recovered from the Panic of 1857, and liquid currency was especially hard to come by in the Yankee economy of Minnesota, Waldmann was sufficiently cash-flush to loan $500 to Christoph and Henry Stahlmann, fellow Bavarians who would later become the region’s most successful lager beer brewers. In exchange, Waldmann received a mortgage on the four lots comprising the core of the Stahlmann’s brewery operations, which later became the center of Schmidt Brewery’s complex of buildings along West 7th Street.

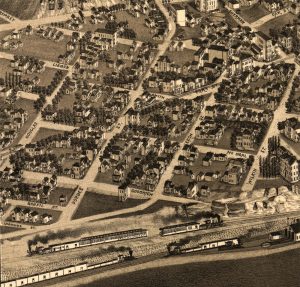

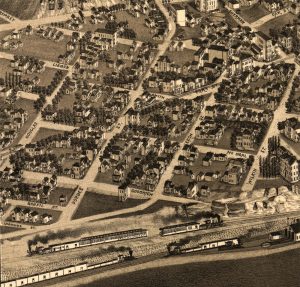

H. Wellge’s hand-drawn 1883 bird’s eye view of Saint Paul, showing Waldmann on Forbes (now renamed Smith)

A steep rise in grain prices during and following the Civil War allowed Waldmann’s flour and feed business to prosper through the 1870s, moving to 66 Fort Street (later renumbered 114 Fort) in 1867, and partnering with Alonzo Eaton beginning in 1876. But by the mid-1870s Waldmann also must have sensed greater opportunities from passive rental income. Gradually he began developing the unused portions of his property immediately to the south of his old saloon building. In 1872, he built the large Italianate Revival house at 457 Smith (extant), near the corner of today’s Smith and Goodrich Avenues, and moved with his wife to this more fashionable house. Two years later, he built a smaller house in between, adding still another unit to the south by 1880 that created a side-by-side duplex (449-451 Smith, razed). When the property belonging to Waldmann’s neighbor immediately to the west was foreclosed in 1879, Waldmann purchased his property, which included a small one-story house facing the alley immediately to the west of the old saloon building (moved to 447 Smith in 1892, then to 41 Douglas in 2015). In all, this gave Waldmann four rentable units by 1880, and enough passive income to support himself and Mina without engaging in any other business.

By the 1880s Waldmann’s health was in decline. Tellingly, the city directories list no occupation for him after 1878. In May of 1881 he made out his will, stating his age as “about 57 years.” Shortly thereafter the Waldmanns moved from their larger house at 457 Smith back to their old saloon building and first home, selling their larger home in April of 1883. This may have been in preparation for the final chapter of their life—their move back to Germany. In April 1885, in the midst of a nationwide depression following the recent crash of the New York Stock Exchange, the Waldmanns sold the last of their real estate to Thomas Manning, a Canadian real estate investor who owned numerous rental properties throughout the City. Anton and Mina then boarded a steamship to Germany. Anton died in June 1886 in Edenkoben, Rhineland-Palatinate, at the age of 62. Mina died thirteen years later (November 1899) in the same village. They never had children, and left no known relatives in the United States.

During the couple’s three decades in the United States, they managed four separate trades, successfully navigating barriers of language, culture and a tumultuous economy. At the end of it all, Anton’s (Leonhard’s) death certificate described him only as a “shoemaker” and a “Catholic;” Mina’s described her only as the latter. Yet the couple left one thing: a humble yet extraordinarily sturdy limestone saloon building, which served as their home, their livelihood and ultimately perhaps as their greatest claim on history.